By Amanda Collins

When something doesn’t go as planned after launch, you can’t pull a spacecraft back into the shop, take it apart and fix it. Often, you can’t even get a glimpse of what’s wrong.

For most people — and companies — the story would stop there.

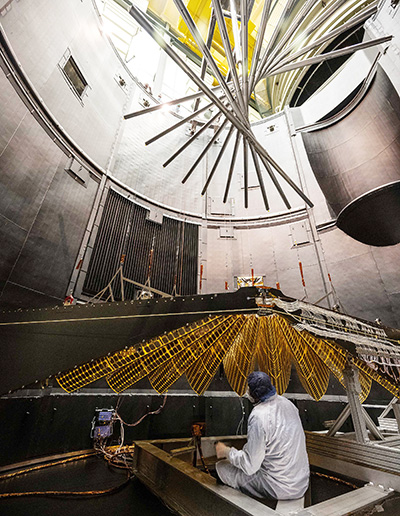

But giving up isn’t an option for the solar array experts on Northrop Grumman’s Deployables team in Goleta, California. When one of the solar arrays on the NASA Lucy mission didn’t fully deploy after the launch in fall 2021, they immediately sprang into action. Lucy uses the UltraFlex array design, which is a flexible blanket that folds like a hand fan and then unfurls in flight to convert sunlight into power.

Zero Visibility

The ambitious 12-year Lucy mission, which is currently ongoing, will visit more destinations in independent orbits around the sun than any other program in history, ultimately targeting Jupiter’s Trojan asteroids. Given this complex journey, the spacecraft must maintain power farther from the sun than any previous solar-powered mission, which is why Lucy also sports some of the largest flexible solar arrays ever built at nearly 24 feet in diameter.

Todd, Northrop Grumman’s technical director for the Lucy solar arrays, was in the parking lot of the Kennedy Space Center after watching the launch when his phone rang with the news that one of the solar array wings had not fully opened.

The challenge was a new one. All of the previous UltraFlex solar arrays had performed flawlessly since their invention by Northrop Grumman in 1990.

“It was a mad dash early on, with everyone trying to put their hands on any piece of data that might mean something, so we could get an answer right away,” said Chief Engineer Dave.

One of the hardest parts for the team — which included subject matter experts from mission partners — was piecing together the puzzle without visual confirmation of what was happening on the spacecraft. Lucy has an onboard science camera, but it wasn’t pointed in the direction of the wing.

“It was like having 20 of the best doctors in the world trying to diagnose what’s wrong with a patient they couldn’t see and with only the patient’s blood pressure and temperature,” said Lucy Solar Array Program Manager Jim.

At Full Tilt

The first step was figuring out how far the solar array had opened.

“We knew the solar array didn’t latch, but we didn’t know how far it was from latching,” said Dave, referring to the way the two end segments click together to secure the array once fully open.

The team devised a way to tilt the spacecraft back and forth to measure the power on all the individual segments, allowing them to develop a math model to determine how far the array had opened. Next, they needed to determine if and how they could further deploy the wing toward latching.

“What impressed me most about the team’s response was witnessing the professionalism, expertise and commitment of everyone — not only here at Northrop Grumman, but from our mission partners as well.”

— Jim, Lucy Solar Array Program Manager

Using a testbed of solar array components that could simulate certain situations, the team established that using the primary and back-up deployment motors at the same time could safely produce enough torque to pull the wing closer to latching.

“The first time we tried a deployment command with both motors, everyone on the team eagerly awaited a data return from the spacecraft,” said Jim. “When we saw that the wing was responding as our modeling and ground testing predicted, we knew we had a path forward.”

Encouraged, the team continued on their path, getting the wing to a tensioned state that the team believes will ultimately fulfill the mission.

A-Team

Looking back at the redeployment effort, the team knows it was made possible by an “A-team effort,” said Todd.

“What impressed me most about the team’s response was witnessing the professionalism, expertise and commitment of everyone — not only here at Northrop Grumman, but from our mission partners as well,” said Jim.

The team’s efforts on the ground recovered the mission, which successfully had its first Earth fly-by in October 2022; the gravity assist from this fly-by set Lucy on a two-year orbit around Earth. The spacecraft will fly by Earth again in December 2024, using that gravity assist to begin its journey to the Trojan asteroids.

Life at Northrop Grumman: Recent Stories

Shape your career journey with diverse roles and experiences that expand your expertise, feed your curiosity, and fuel your passion.

Life at Northrop Grumman: Archived Stories

It takes every one of us to make the impossible a reality. See what life is like at Northrop Grumman.